Friday Footnotes: Unlucky numbers, musical cephalopods, and dangerous potatoes

A collection of things I learned or found interesting recently

Welcome to this week’s Friday Footnotes!

Apologies for the small error in question 17 of this week’s Weekly Quiz! I originally asked you for a six-letter word, when the answer I was looking for was a seven-letter word. Thanks to everyone who messaged me quickly, so I was able to fix it in the post itself, but of course I could not amend the emails that had already been sent out. It was nice however to see an example of Cunningham’s Law in action: “The best way to get the right answer on the Internet is not to ask a question; it’s to post the wrong answer.”

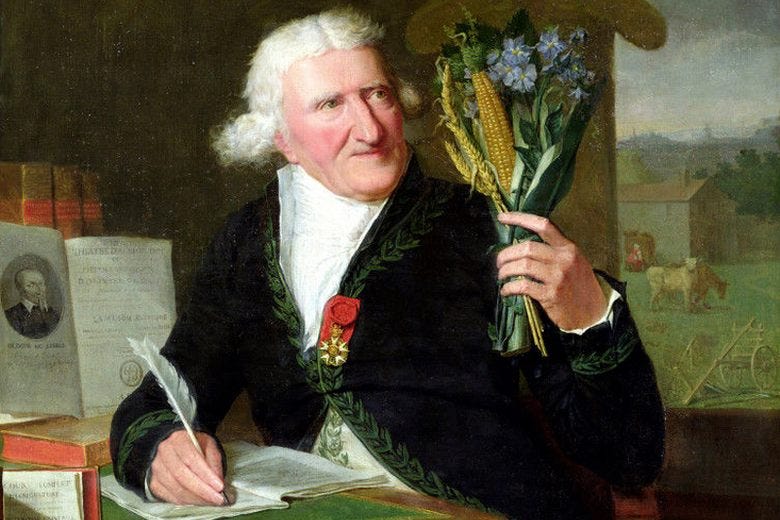

The cultivation of potatoes was banned in France until 1772, as it was believed that potatoes caused leprosy. This belief persisted in some parts of the medical establishment throughout Europe until the early 19th century. During the Seven Years War (1756-63), French pharmacist Antoine-Augustin Parmentier was wounded and captured by the Prussians five times(!) and while imprisoned was fed nothing but potatoes, which were only used in France for animal feed at the time. But he was surprised to find himself remaining healthy and strong (and leprosy-free) and when he returned to France after the war, he began advocating for the potato as a food source.

Parmentier devised a number of publicity stunts to rehabilitate the reputation of the potato. He hosted dinners featuring potato dishes for prominent figures including Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and Antoine Lavoisier and he gave bouquets of potato flowers to Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. He also planted a field of potatoes on the outskirts of Paris and paid guards to protect them during the day to give the appearance that they were protecting something valuable, but then withdrew the guards at night to allow hungry locals to steal the potatoes. In 1773, the French parliament repealed the ban on potatoes, and 12 years later potatoes helped stave off a bad famine in northern France after a bad harvest year.

Parmentier’s name lives in on a few potato dishes in French cuisine, including hachis Parmentier, a kind of shepherd’s pie, and the delicious Parmentier potatoes:

In Italy, the unlucky day is not Friday the 13th, but Friday the 17th. Apparently this can be traced to the fact that 17 in Roman numerals, XVII, can be shuffled to spell vixi, which in Latin means “I have lived”, implying death. For example, the 2000 parody film Shriek if You Know What I Did Last Friday the Thirteenth was released in Italy with the title Shriek - Hai impegni per venerdi 17? (Shriek - Do you have any plans for Friday the 17th?).

I watched this 18-minute video of a Swedish musician painstakingly trying to teach an octopus “to play the piano”. It’s a great watch, and the sort of thing that typifies why YouTube is great. I think the most fascinating part to me was the problem-solving approach, the gradual testing, iteration, testing, iteration, the need to consider how an octopus differs from us, how to communicate across those differences, what an octopus might be motivated by, the application of reinforcement learning, and above all, the progress that can be made with patience, persistence and incremental improvement.

I also read this week about Mary Catherine Bateson (1939-2021), an American writer and cultural anthropologist who was the daughter of anthropologists Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson. Her parents met in New Guinea while conducting field work (Mead is the author of Growing Up in New Guinea and Coming of Age in Samoa among other works). When Mary was born, her birth was recorded on film (more field work) and her paediatrician was none other than Dr Benjamin Spock1, of The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care fame. Mary Catherine Bateson became an anthropologist and writer herself, including writing a 1984 biography of her parents, but is perhaps best known for her 1991 book Composing a Life, which explored her own life and the lives of four of her friends to outline the stop-start nature of women’s lives and the need to find meaning while adapting to changing circumstances. She used the metaphor of life as a work in progress, an ongoing improvisatory composition that evolves over time. The book was hailed as an inspiration by Jane Fonda and Hillary Clinton among many others, and is more relevant than ever as more people are pursuing lives and careers that are not linear or predictable:

”It is time now to explore the creative potential of interrupted and conflicted lives, where energies are not narrowly focused or permanently pointed toward a single ambition. These are not lives without commitment, but rather lives in which commitments are continually refocused and redefined. We must invest time and passion in specific goals and at the same time acknowledge that these are mutable. The circumstances of women’s lives now and in the past provide examples for new ways of thinking about the lives of both men and women. What are the possible transfers of learning when life is a collage of different tasks? How does creativity flourish on distraction? What insights arise from the experience of multiplicity and ambiguity? And at what point does desperate improvisation become significant achievement? These are important questions in a world in which we are all increasingly strangers and sojourners. The knight errant, who finds his challenges along the way, may be a better model for our times than the knight who is questing for the Grail.”

Spock is another surprise Olympian: he was part of the gold medal-winning US men’s eight rowing team at the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris.