Friday Footnotes: Extraordinary lives, subversive ads, and more musical writers

A collection of things I learned or found interesting recently

Welcome to this week’s Friday Footnotes!

A quick note on scheduling: as of this month, Friday Footnotes will switch from weekly to fortnightly, with every second Friday instead being the release day of the longer monthly quizzes for paid subscribers.

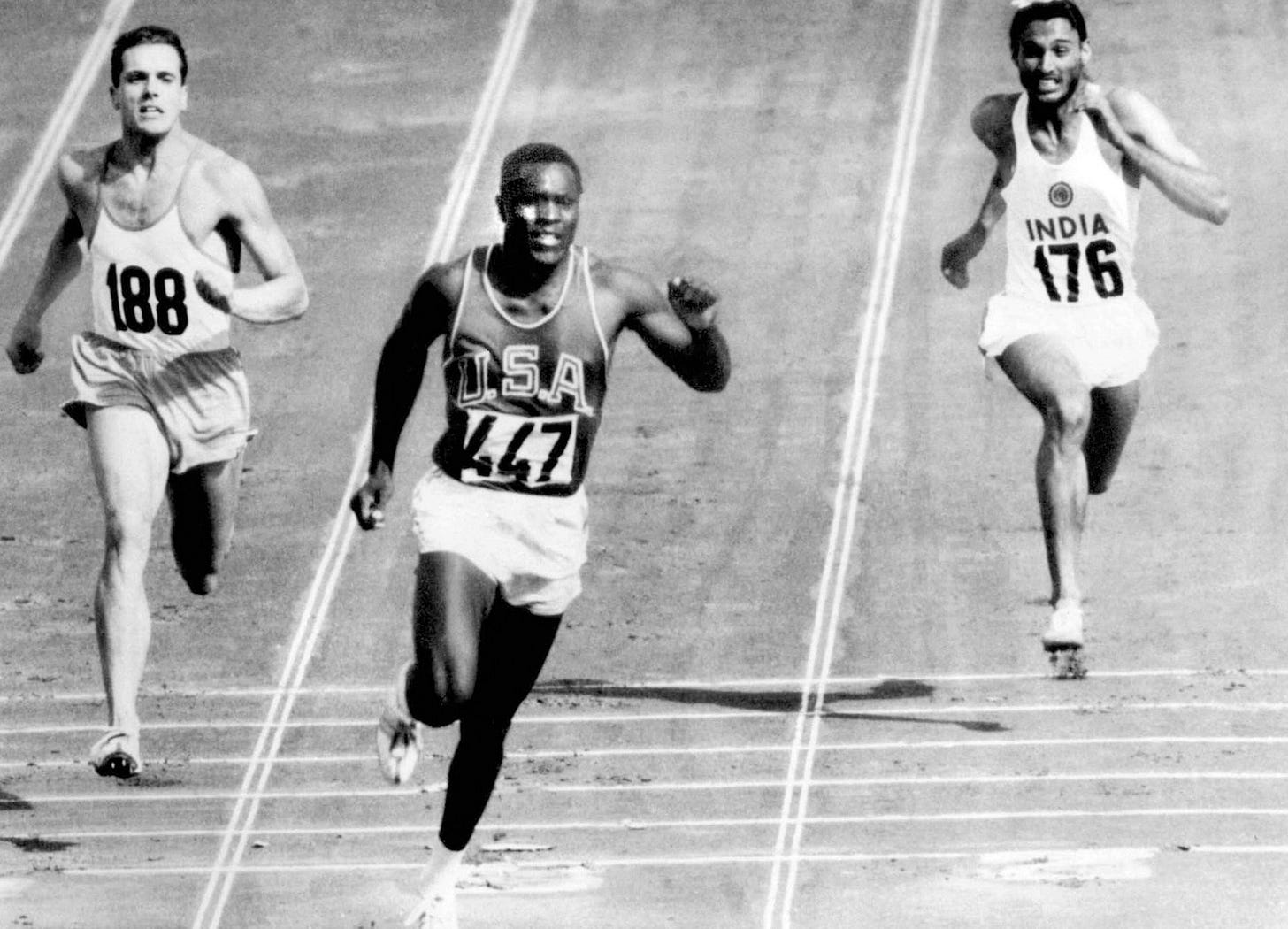

This week I learned about Rafer Johnson (1934-2020), who is surely the only person to have done all of the following: won an Olympic gold medal, appeared in an Elvis Presley film (Wild in the Country, 1961), appeared in a James Bond film (Licence to Kill, 1989), and lit the Olympic cauldron at an Opening Ceremony, doing so at the 1984 Los Angeles Games.

Johnson won his gold medal in the decathlon in Rome in 1960, where he was also the flag bearer. In 1958-59 while student body president at UCLA, he also played basketball under legendary coach John Wooden, and in 1959, he was drafted by the Los Angeles Rams as an NFL running back, though he never ended up playing in the league.

Despite all of that, perhaps his most significant moment came in 1968 when, standing with Robert Kennedy at the Ambassador Hotel, he helped to apprehend and disarm Sirhan Sirhan after he shot Robert F. Kennedy. Johnson called the assassination “one of the most devastating moments of my life.” The same year, he served on the organising committee of the first Special Olympics in Chicago, and he founded the California Special Olympics the following year. A remarkable life.I was also reminded about Pearl Kendrick (1890-1980), who I first read about a few years ago in Matt Ridley’s How Innovation Works. Together with Grace Eldering, Kendrick developed the first whooping cough vaccine, as well as a reliable method for testing which patients were infectious using a cough plate. In 1932, the pair were working in Grand Rapids, Michigan at the state public health laboratory analysing the safety of water and milk. There was a widespread whooping cough outbreak in the city at the time, and Kendrick asked her boss if they could work on it after hours. They developed a cough plate where they could test who was infectious and went door to door collecting samples after a full day at their real jobs.

Over the next four years, they gradually developed an effective vaccine, testing it on themselves to prove it was safe. They set out to prove it more widely, but wanted to avoid the standard practice at the time of using orphans as a control group who were denied the vaccine(!). With the help of doctors and social workers, they found matching groups of people who had received the vaccine and those who had missed out.

The pair received little recognition or financial reward for their work, and they shared their methods globally. As Matt Ridley writes, “They did everything right: chose a vital problem, did the crucial experiments to solve it, worked with communities to test it, gave it to the world and wasted no time or effort defending their intellectual property.” Shortly after Kendrick’s death, Michigan University Public Health Dean Richard Remington wrote:

”A life saved by prevention cannot even be identified. Who are the men and women living today who would be dead from whooping cough had it not been for Pearl Kendrick’s vaccine? We can conclude with reasonable certainty that several hundred thousand of them are now leading productive lives, in this country alone. But who are they? Name one. You can’t do it and neither can I.…The accomplishments of disease prevention are statistical and epidemiological. Where’s the news value, the human interest in that? … But a public service orientation can provide more than ample compensation. Dr. Kendrick never became rich and, outside a relatively small circle of informed friends and colleagues, never became famous. All she did was save hundreds of thousands of lives at modest cost. Secure knowledge of that fact is the very best reward.”Following on from last issue’s Gorbachev Pizza Hut ad in the 1990s, I learned that Gorbachev also featured in a 2007 Louis Vuitton ad. What made the ad more interesting, however, is that the document sticking out of his bag is a publication with the headline, “The Murder of Litvinenko: They Wanted to Give Up the Suspect for $7,000.” It references the former KGB spy who was poisoned a year earlier in Britain with radioactive isotope polonium-210. Louis Vuitton declared, “Our company has absolutely no intention to pass any other messages than the one on ‘personal journeys’,” and a representative for Gorbachev said he was also unaware of the contents of the magazine.

Last Friday Footnotes I also looked at the the composing work of writers and philosophers Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Friedrich Nietszche. Anthony Burgess, author of A Clockwork Orange (1962) among other works, was also a prolific composer, writing more than 250 works including symphonies, concertos, piano music, and theatre works. In fact, Burgess wrote of himself, “I wish people would think of me as a musician who writes novels, instead of a novelist who writes music on the side.”

The piano was his main instrument, and among his compositions is a 1985 set of 24 Preludes and Fugues reminiscent of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, which he titled The Bad-Tempered Electronic Keyboard. You can listen to some of his piano pieces here: